Rewiring My Fashion Practice: Reflections on Systems Thinking and Sustainable Futures

Share

Introduction: Stepping Back to Reflect on the Rewire Module

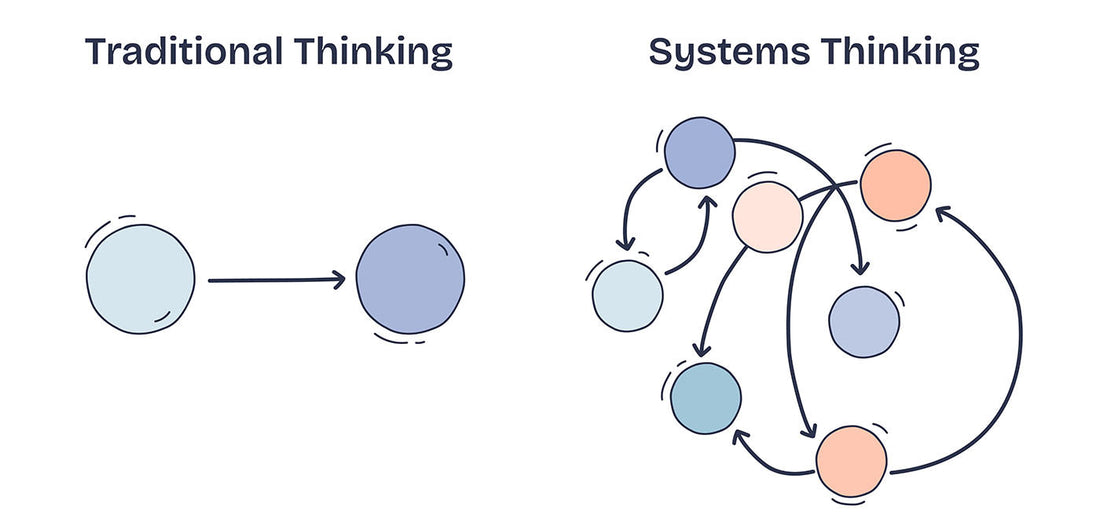

The second module of my online MA in Fashion Sustainability at Falmouth University in Cornwall was titled Rewire. The title could not have been more appropriate, because that is precisely what happened to my way of thinking. The module centred on systems thinking, a framework that asks us to look at fashion not as isolated objects but as networks of connections between people, resources, politics, culture and ecology.

I had planned to write a weekly diary to record my journey, but the intensity of the course, the community engagement required, and my own commitments made that impossible. Instead, I now find value in stepping back, taking a breath, and reflecting in depth on the entire module before the next one begins. This piece is both a personal diary and a contribution to wider conversations about sustainable fashion in Singapore, the UK and beyond.

Systems Thinking: Seeing Fashion as Interconnected

One of the most transformative aspects of Rewire was discovering systems thinking. Through exercises such as the Rich Picture and the Cluster Map, I learned to visualise fashion not as a straight line from design to consumer, but as a web of interdependent actors and consequences.

Mapping something as ordinary as a T-shirt suddenly revealed farmers, spinners, dyers, factory workers, shipping routes and consumers in London or Singapore, all bound together. What I once saw as a chain revealed itself as a living, shifting network.

Community conversations reinforced this perspective. People spoke about affordability, identity and trust in brands. Their voices reminded me that fashion is not only about clothing, it is about belonging, aspiration and survival. I drew on systems thinking to connect these voices to the broader picture of fashion and the ways it can change.

Fashion and Ecosystems: From Extraction to Regeneration

The module also asked me to consider fashion’s place in ecosystems. For decades, the industry has taken resources such as water, cotton and oil, and given back pollution and waste.

Learning about concepts such as Cradle to Cradle design and reflecting on the example of Patagonia compelled me to confront the harm that fashion causes. My own ecological footprint, which I once thought was modest, was revealed to be larger than I had assumed. Importing fabrics, occasional online purchases, and daily energy use all had hidden costs. These overlooked impacts embodied what environmental scholar Rob Nixon describes as “slow violence”, harm that builds gradually and often remains invisible until it causes lasting damage.

At the same time, the module offered hope. Regenerative fashion, which gives back to nature rather than simply taking less, invited me to imagine fashion as a healing practice.

Accountability Through Certifications

Another theme of Rewire was the rise of certifications and eco-labels. At first, they seemed to promise clarity, but the more I studied them, the more complex they became. Certifications such as GOTS or Fairtrade provide clear standards, yet misleading greenwashing labels confuse consumers and enable brands to appear sustainable without genuine accountability.

Certifications such as GOTS and Fairtrade ensure accountability within the scope of their standards, but they only cover part of the industry. What we truly need is policy that makes accountability mandatory across entire supply chains, so that transparency and responsibility are no longer optional but expected of every brand.

Rethinking Fashion Economics

The module challenged me to rethink economics and introduced me to Doughnut Economics, a framework Kate Raworth created to reimagine economies that thrive within ecological boundaries while also meeting social needs.

Doughnut Economics presented a striking contrast to the growth-driven models I had always associated with success. I began to ask myself if fashion could function differently. Could sufficiency be more valuable than excess? Could degrowth be credible in an industry that has relied for so long on expansion?

Personally, this raised tensions. As a designer, I want to grow in my career. Yet growth in the traditional sense often comes at environmental and social costs. Conversations in Singapore and the UK highlighted the real-world challenge of affordability. Many people try to shop more responsibly, yet rising costs push them out. The lesson was clear. Regenerative fashion must not only be possible but also accessible.

Fashion as Political Practice

The module introduced me to the idea that fashion is political. Regulations, trade policies and activism all shape it, and through Rewire I studied the concept of design as politics, developed by Tony Fry. Every design choice, from fabric to pricing, directs how we use resources and decide who benefits.

Global frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals demonstrate fashion’s role in international targets. My community conversations, however, added another layer to this teaching. In Singapore, people explained that hierarchical structures place power in top down decision making and give little space to grassroots initiatives. They felt that meaningful change must therefore work within accepted cultural frameworks and flow through carefully designed educational outreach.

The course content introduced me to design as politics, but the community voices helped me see how political structures shape fashion in practice. In Singapore, fashion’s political role depends less on direct activism and more on respectful outreach that connects education, policy and culture. Rewiring the system means learning to work with these structures to achieve impact from within.

Culture, Heritage and Collaboration

The cultural strand of Rewire asked me to consider heritage, appropriation and respect. Fashion has a long history of taking inspiration from Indigenous and traditional practices without acknowledgement. This module challenged me to think about what respectful collaboration could look like.

Projects that give refugees and craftspeople the opportunity to share their heritage moved me, because they sustain both community and craft.

In my own community engagement, I heard stories from makers whose textiles carried the weight of history, migration and resilience. These conversations reminded me of my responsibility as a designer to honour and not exploit cultural traditions.

Fashion as Spatial Activism

One of the more surprising insights from Rewire was the connection between fashion and place. Through the concept of creative placemaking, I began to see how fashion can shape neighbourhoods and local identity.

In Singapore, people spoke about the loss of spaces for craft. In the UK, others highlighted how high streets dominated by fast fashion chains are erasing independent voices. Both contexts revealed that fashion can either nurture or undermine a sense of belonging. For me, this reframed design. It is not only about garments but also about the places and communities that fashion helps to shape.

The Human Dimension: Empathy and Values

Beneath every system are people, and empathy became one of the most valuable lessons of Rewire. We studied the ethical purchasing gap, which refers to the discrepancy between what people claim to value and what they actually purchase. Rather than seeing this as hypocrisy, I began to understand it as a reflection of the pressures of everyday life.

Developing empathy also meant examining myself. I recognised my own biases and learned to appreciate the differences between Singaporean and British contexts. This self-awareness is as critical as any academic framework. It allows me to approach sustainable fashion with humility as well as determination.

Waste as Opportunity

Towards the end of the module, the subject turned to waste. Fashion generates enormous volumes of discarded textiles, much of which is of low quality and difficult to recycle. It is a daunting challenge.

Yet the idea that waste can be a resource shifted my perspective. Designers such as Angel Chang, who draw on Indigenous knowledge to create low-impact collections, show that circularity can be achieved.

Community conversations mirrored this urgency. In Singapore, the issue of limited space makes waste management a pressing concern. In the UK, charity shops are overwhelmed with unwanted garments. Both cases demonstrate that fashion must be redesigned to prevent waste at its source.

Conclusion: Carrying the Lessons of Rewire Forward

Reflecting on Rewire, I can see how the module lived up to its name. It rewired my perception of fashion, moving me from seeing it as an industry of products to recognising it as a system shaped by ecology, politics, culture and people.

As a student on the online MA Fashion Sustainability at Falmouth University, I have grown into someone who is not only a designer but also a facilitator of change. My community engagement taught me that listening is as essential as creating, and that collaboration is as vital as innovation.

Fashion connects to wider systems, and these connections create both risks and possibilities. I continue to rewire my practice not as a single act but as an ongoing process. Rewiring is not a single act but an ongoing practice.

For educators, this reflection demonstrates the value of connecting theory to lived experience. For students, I want to highlight the importance of personal voice in academic work. And for anyone who cares about the future of fashion, I offer this reminder. The journey towards sustainability is both collective and personal. It begins with rewiring how we see the world, and it continues with how we choose to act within it.

🌿🦋 Join My Free Online Classes

I am so excited to share a series of free online classes designed to help you connect more consciously with your clothes and the textiles around you. Together, we will explore simple, creative skills such as making natural pigments straight from your kitchen, easy sewing hacks to breathe new life into worn garments, and beginner-friendly patchwork to transform old clothes into beautiful household textiles.

These classes focus on empowerment, creativity, and sustainability. Join me, whether you are just starting your journey or deepening your connection with fashion sustainability, and together we will learn, make and reimagine.

🌸🌱 Wilde Reads: Books for Change

Until now, Wilde Reads has mostly been me sharing what I am reading and reflecting on, but I would love to turn it into something more collective. If you are passionate about sustainability and fashion, I would be delighted for you to read alongside me. Together we can explore books that spark fresh ideas, open meaningful conversations and inspire more conscious ways of living.

We are now on our eighth book, Fibershed by Rebecca Burgess with Courtney White. It is a powerful exploration of the growing movement of farmers, makers and fashion activists working to create a new regenerative textile economy. If this resonates with you, I would love for you to join me in turning the page towards a better world. 📚✨

With gratitude,

Tala 🌿💚